One of the most recognizable sharks is the Hammerhead shark, evolutionarily earmarked with a set lateral projections, called cephalofoils, off the sides of their heads that allows them to have a 360° visual radius on the vertical spectrum. Even though these projections are highly beneficial while hunting, they do tend to make the shape and characteristics of the animal quite distinct. Despite this unique hunting advantage with their visual acuity, there is some disadvantage handed to the hammerhead, with their mouths smaller than the average of the rest of their body, an anomaly among sharks.

Species Variant

There are nine variants of hammerhead shark and an additional species that is similar. The Winghead shark, native to the South Asian coastal waters, has larger cephalofoils than any other hammerhead sharks, though they are smaller than the largest of the hammerhead sharks, the Great Hammerhead. The other hammerhead species are the Bonnethead, the Great Hammerhead, the Scalloped hammerhead, Carolina hammerhead, Scoophead shark, Smalleye hammerhead, Smooth hammerhead and the Whitefin hammerhead.

Anatomy

On an average basis, the hammerhead shark ranges from 1m to 6m+, with the largest being the Great Hammerhead. They can range in weight from 3 to 550 kg. The hammerhead family ranges from dark brown to grey on their dorsal side and have a grey or white belly, sometimes even olive in colour which performs as a sort of camouflage while hunting. Previous to scientific research, it was thought that the cephalofoils were used to enhance poor vision in the shark but studies have shown that not only do the hammerheads have excellent vision but also possess the ability to turn quickly and sharply due to the the aided maneuverability the cephalofoils provide. It has been considered that the hammerhead evolved the cephalofoils due to the unusually small mouths they have.

Like all sharks, hammerheads have electroreceptor sensory pores called ampullae of Lorenzini, allowing them to sense electromagnetic pulses from prey, making them one of the most deadly predators in the ocean. The shape of their mallet like head also allows them to scan wider areas of the ocean floor in search of prey, acting almost like a radar.

Diet

The hammerhead is an active hunter rather than a scavenger, choosing to hunt around dusk when the sunlight works to the advantage of the shark. The hammerhead consumes invertebrates, jellyfish, crabs and octopi, as well as other bony fish. While they will eat nearly any animal in the ocean, the hammerhead seems to prefer the stingray. There have been records indicating the hammerhead also performs cannibalism among their own or other family species.

Habitat

All hammerhead sharks are coastal swimmers, swimming out into ocean depths no deeper than 300m. They are distributed over circumtropical water, clinging to the coasts of nearly all continents within warmer waters. Along the western Atlantic they flow from North Carolina down to Uruguay, from Baja California down to Peru along the eastern Pacific, all along the western Pacific and also inhabit the Mediterranean Sea region and the Indian Ocean region.

Reproduction

All hammerhead sharks are viviparous, meaning they hatch their eggs internally then give birth once their pups are strong enough. The pups sustain life internally through a nutrient rich yolk sac similar to a placenta in mammals. An oddity of the hammerhead shark is that they often tend to give birth in the Northern Hemisphere, usually during spring or summer. Hammerheads, dependent upon species, give birth to anywhere between 6 and 40+ pups, dependent upon size of the shark.

Once born the adults abandon their pups, requiring them to survive on their own. The pups often travel toward warmer waters, huddling together for warmth and protection. Once they’re large enough, the pups separate, though they will remain in schools of other hammerheads unless they hunt.

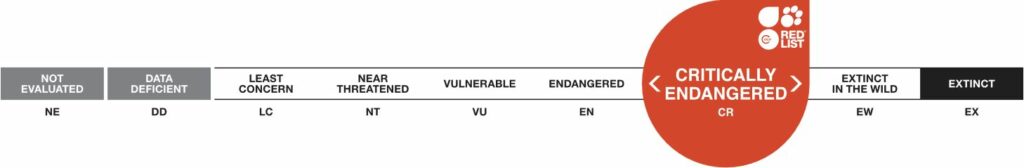

Conservation Status

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the Great and Scalloped are listed as endangered and the small eye hammerhead is listed as vulnerable. The reason for their statuses is overfishing, as their fins are considered a delicacy. In 2013, three endangered commercially valuable sharks, the hammerheads, the oceanic whitetip and porbeagle shark, were added the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, a multilateral treaty that added more protection and regulation of of endangered species. This is considered a first step toward allowing the hammerhead population to surge once again.